Did you know that there is a Shrewsbury road named after two Victorian taxidermists? It is Shaw Road, in Monkmoor, whose name is a memorial to Henry Shaw (1812-1887), and his brother John (1816-1888). [footnote 1]

Good taxidermists were very much in demand in Victorian Britain. Natural history was becoming increasingly popular, particularly amongst the upper and middle classes. The Victorians were also great collectors, and it became fashionable to own a collection of stuffed animals and birds. In addition, bird watching was hampered by the difficulty of identifying birds without binoculars. The ‘binocular telescope’ was first invented by Galileo, but it was not till the development of much improved optics in Germany from the 1890’s, and the development of modern lightweight materials in the twentieth century, that binoculars became practical and affordable for bird watching. [footnote 2]. Thus, to be sure of the identity of a rare bird, the Victorian naturalist had to shoot it, and it would then be stuffed and added to a collection.

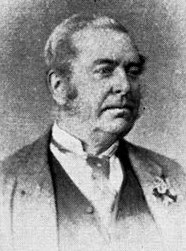

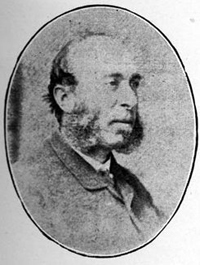

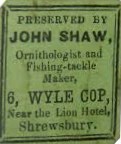

Henry and John Shaw’s father was a taxidermist in Shoplatch, and both boys followed him into the trade. Henry was the sociable one – tall, well-built and immensely strong, he loved country sports, especially fishing, and was a fount of knowledge about all things to do with natural history. John was very different, being quiet, fastidious and a bit prickly until one got to know him. After their father’s death, the brothers worked as partners in the business, but in due course they went their separate ways, and each set up his own shop. Henry’s business was at 45 High St, while John eventually settled not far away at 82 Wyle Cop.

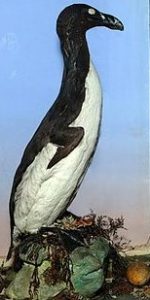

Henry, owing to his more genial nature, got on much better that John with the country gentlemen, and thus secured most of them as his patrons. He mounted and arranged collections of birds for John Rocke at Clungunford (which finished up in Ludlow Museum), Col. Wingfield at Onslow, Earl Powys at Powys Castle, Mr Naylor at Leighton Hall, the Duke of Westminster at Eaton Hall, and the Duke of Portland at Welbeck Abbey, among others. In addition, Lord Hill appointed him curator of his collection at Hawkstone at an annual salary. As a result of this work Henry Shaw became very prosperous and well known throughout the country. His fame resulted in him being entrusted with no less than three specimens of the then exceedingly rare, and now extinct, Great Auk, one of which is displayed in the new Shrewsbury Museum. When Henry died in 1887, his business was continued successfully by his son, Harry, but it did not long survive his untimely death in 1896. [footnote 3]

John Shaw’s biographer wrote this about him. ‘Although not called away so much as his brother, he had a large business connection throughout the County, and far beyond. He was a man…confident of his own ability, who liked his customers to have confidence in him, and this, it generally turned out, was not misplaced… Those – and they were many – who could see through his superficial manners, found that they formed but a thin veneer concealing a thoroughly genial and kindly disposition. He was an art critic of no mean ability, and more than one local artist owed his rise to fame to the discriminating taste of John Shaw.’ [footnote 4]

Footnotes

[1] Full biographies are from Fauna of Shropshire by H.E. Forrest 1899

[2] http://www.europa.com/~telscope/binohist.txt