I can’t remember now how I first found Henry Pidgeon’s diary, written between 1823 and 1830 (SA 6001/3055-3058), but it has proved both enjoyable and informative. Henry Pidgeon (1806-71) is best remembered for his guidebook ‘Memorials of Shrewsbury’ which ran through many editions, but he was also a retail chemist in the High Street, and Borough Treasurer for 31 years.

As I am a retired GP, the first entry in the diary immediately caught my interest. It reads,

Jan 11th 1823 – ‘The small pox and measles are very prevalent in our town, especially among the lower orders of people, the dwellings of which in general are not kept clean and properly ventilated.’

As a follow up he wrote later,

Feb 27th – ‘On referring to the registers of three of our four churches, it is found that there have been 70 interments in the Parish of St Chad, 56 at St Mary, and 28 at St Julian’s since the 1st of January. There were 8 graves opened in one day in St Chad’s church gardens.’

A question formed in my mind as I read these entries. This was – ‘Is any way of proving or disproving Pidgeon’s contention that the epidemic was worst ‘especially among the lower orders of people, the dwellings of which in general are not kept clean and properly ventilated’?’

The epidemic in St Mary’s parish

To try to answer this I turned first to the parish registers. As well as St Chad’s, St Mary’s and St Julian’s parishes mentioned by Pidgeon, I also looked up St Alkmund’s and the Abbey (Holy Cross) for comparison. I had an unexpected stroke of luck, as the Vicar of St Mary’s had noted those who had died of measles and smallpox in the margin of the burial register. This showed that the deaths from measles and smallpox in St Mary’s parish continued until the month of May, so I decided to note the details of all the deaths in all the parishes in the period January 1st to June 30th. The results for the measles and smallpox deaths in St Mary’s are in Figure 1.

To try to answer this I turned first to the parish registers. As well as St Chad’s, St Mary’s and St Julian’s parishes mentioned by Pidgeon, I also looked up St Alkmund’s and the Abbey (Holy Cross) for comparison. I had an unexpected stroke of luck, as the Vicar of St Mary’s had noted those who had died of measles and smallpox in the margin of the burial register. This showed that the deaths from measles and smallpox in St Mary’s parish continued until the month of May, so I decided to note the details of all the deaths in all the parishes in the period January 1st to June 30th. The results for the measles and smallpox deaths in St Mary’s are in Figure 1.

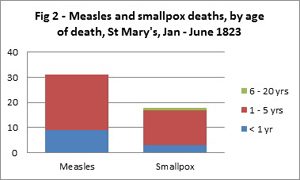

I further analysed the figures to show the age of death (Figure 2).

What is immediately striking is that for both diseases all but one death occurred in the under 5’s. This immediately calls into question Pidgeon’s contention that it was ‘the unventilated dwellings of the lower orders’ that was the major factor causing deaths, since people of every age lived in the same houses. Pidgeon believed, like most people at that time, in the ‘miasma’ theory of the causation of disease, whereby illnesses were thought to be brought about by suspended particles of decaying matter characterised by a foul smell. But we now know that infectious diseases are caused by germs, and when there is an outbreak of a potentially fatal infectious disease people either die or fight it off. Those who recover are then immune to the disease, and it then takes several years for a new cohort of non-immune children to come along to provide a reservoir for a new epidemic.

What is immediately striking is that for both diseases all but one death occurred in the under 5’s. This immediately calls into question Pidgeon’s contention that it was ‘the unventilated dwellings of the lower orders’ that was the major factor causing deaths, since people of every age lived in the same houses. Pidgeon believed, like most people at that time, in the ‘miasma’ theory of the causation of disease, whereby illnesses were thought to be brought about by suspended particles of decaying matter characterised by a foul smell. But we now know that infectious diseases are caused by germs, and when there is an outbreak of a potentially fatal infectious disease people either die or fight it off. Those who recover are then immune to the disease, and it then takes several years for a new cohort of non-immune children to come along to provide a reservoir for a new epidemic.

Variations between parishes

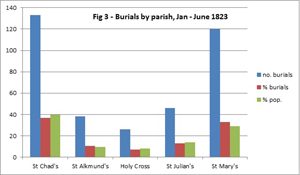

While searching the Archives’ online catalogue for more information about Henry Pidgeon, I found another reference entitled, ‘Obituary notices and events etc in Shrewsbury’ by David Parkes, with additions by Henry Pidgeon’ (SA 6001/155). This has a record of the population of the town by parish for the year 1821. Using these figures and my results for burials in the period Jan-June 1823, I was able to construct the following table (shown graphically in Figure 3).

While searching the Archives’ online catalogue for more information about Henry Pidgeon, I found another reference entitled, ‘Obituary notices and events etc in Shrewsbury’ by David Parkes, with additions by Henry Pidgeon’ (SA 6001/155). This has a record of the population of the town by parish for the year 1821. Using these figures and my results for burials in the period Jan-June 1823, I was able to construct the following table (shown graphically in Figure 3).

| Parish | St Chad’s | St Alkmund’s | Holy Cross | St Julian’s | St Mary’s | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population (1821) | 7213 | 1707 | 1444 | 2556 | 5328 | 18248 |

| % of town population | 39.53 | 9.35 | 7.91 | 14.01 | 29.20 | |

| Total burials | 133 | 38 | 26 | 46 | 120 | 363 |

| % of burials | 36.64 | 10.47 | 7.16 | 12.67 | 33.05 |

Some of the numbers are small, but it appears that the burials in each parish were more or less in proportion to its population. In other words, the epidemic did not appear to be more serious in one parish than another.

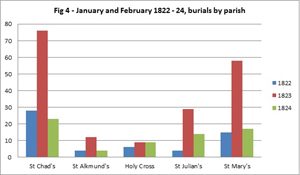

To try to get a different angle on the figures, I widened my search, this time counting deaths in all parishes in just January and February in the years before and after 1823. The results are shown in Figure 4.

To try to get a different angle on the figures, I widened my search, this time counting deaths in all parishes in just January and February in the years before and after 1823. The results are shown in Figure 4.

From these figures it appears that the parish of Holy Cross seems did not suffer a higher proportion of deaths in the epidemic of January and February 1823, whereas all the others did. Why might that have been? There are two possibilities – either fewer of the Holy Cross residents became ill, or else more of those who did become ill recovered. We have already noted that it seemed to be age (and hence lack of immunity), not place of residence, which determined who got the disease. So might it be that greater affluence, which would tend to favour better care of the sick, made a difference as to whether sufferers died or recovered? At that time, the town centre parishes – St Chad’s, St Alkmund’s, St Julian’s and St Mary’s – all had a mixture of social classes. The parish of Holy Cross, however, was completely outside the town centre, and hence probably had fewer poor people. This suggests that relative affluence may have favoured a lower mortality rate in this parish, but not having detailed demographic information makes this only a possibility.

Caring for the sick

So is there another way we can glean any evidence that better care helped some people to avoid death? I found an article in the Shrewsbury Chronicle of February 28th 1823 describing the epidemic. Part of it reads,

‘During the above noticed mortality, the measles attacked nearly all the children in our House of Industry. From 17 to 20 were generally ill at the same moment; yet by the regular and skilful medical attendance and domestic management in the Establishment, every case was successful – not one death occurred.’

At that time the regime at the House of Industry was much less stringent than in the later workhouse, and many of the residents would have been better fed and cared for than those who lived in poverty in the community. The evidence is anecdotal, but, for measles at least, it suggests that better nutrition and care had some influence in helping sufferers survive the disease.

Another smallpox epidemic

But how about smallpox? Is it possible to glean any further Shropshire information about the nature and spread of this disease, which had a fearsome reputation as a killer, irrespective of social class? An online search of the Archives led me to a number of letters in the Attingham collection. These date from an earlier period, the 1740s and 1750s, the time when Thomas Hill owned Tern Hall (the forerunner of Attingham Hall). Thomas Hill’s steward, Thomas Bell, described an outbreak of smallpox that started in Atcham and then spread to the community at Tern Forge. The Forge was then a profitable enterprise situated near the Hall, whose workers lived in better accommodation that those in the town (Fig 5)

On April 15th 1752 Bell wrote,

‘Smallpox is in no more families than when I wrote last – two in Atcham and four at Tern works…In the four families at the works there are nine sick and three or four of them [are] in a dangerous way and nineteen more at the works that have not yet had them.’

Seven days later he wrote that,

‘[the smallpox] are broke out in two more families at the works, since my last [letter], but there and at Atcham they are generally of that sort called wart pox and another sort that are similar and by what I am told are the most favourable kind and not so infectious as other sorts. But I am afraid they will not be over suddenly, for as there are still about 15 or 16 at the works that are not yet sickened and that houses in such a cluster…it’s very likely to go through the whole.’

Over the next month Bell described the epidemic gradually finishing, first in Atcham, and then at the Forge. On May 25th he concluded,

‘I have just now been at the works and find that every child that had not had the smallpox is now sickened, excepting one about 6 months old…, so that all must be over there in a fortnight.’(SA 112/12/Box 23, letters 44, 45, 52).

These reports illustrate that in the closed forge community, all the children except one infant (presumably still immune from its mother’s antibodies), got the disease. The letters also tell us that Bell, like many others at that time, realised that smallpox came in various forms, some more lethal than others. Thomas Hill also understood this, writing earlier about his daughter,

‘Little Sukey is recovering of ye smallpox. She has had a very kindly sort and favourable, but most in her face’ (Thomas Hill to Rowland Hill, 8.6.1749, SA 112/12/Box 21/336).

We now know that there are different types of smallpox (called variola major and minor), with a different prognosis. So we can understand why Thomas Hill and Thomas Bell noted that the outcome of the illness did not depend on the conditions that the patient lived in (as Henry Pidgeon thought), but on the type of infection.

But it was understandable that Pidgeon should link the epidemic of measles and smallpox to poverty and poor social conditions, for it was well known that the poor generally died much younger than those classified as ‘gentlemen or professionals’ (Table 2). My study has also found some evidence that better nourishment and medical care may have improved the outcome in measles. But it has also been shown that smallpox affected all the susceptible individuals in the population, irrespective of wealth and hygiene.

|

No of deaths |

Average age of death of persons in this class |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1850 |

1851 |

1852 |

|

|

| Gentlemen, professionals and their families |

11 |

22 |

15 |

48 |

| Tradesmen and their families |

117 |

129 |

78 |

38 |

| Labourers and their families |

87 |

118 |

87 |

34 |

Facts such as these were used by forward-thinking doctors after the 1840s to provide support for the germ theory of disease. But understanding the cause was just a start. It would be well over a century before smallpox would be eliminated and measles controlled. And all this has come about through immunisation, not an improvement in social conditions, which would probably have surprised Henry Pidgeon.