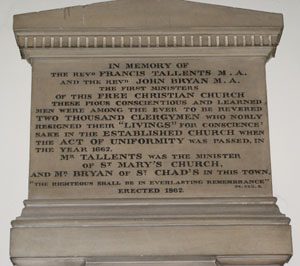

Those of you who are sharp-eyed may have noticed the same date – 1662 – above two of the old churches in the town, the Unitarian in High Street and the old chapel in Dogpole. Why should the builders of these churches wish to record this date?

Two exceptional Presbyterians

One significant outcome of the Parliamentary victory in the English Civil War was a change in the way that the Church of England was governed, the previous government by bishops (Episcopalian) being replaced by a Presbyterian form in 1650. Presbyterians believe that church government should be shared by both ministers and lay people, in particular that lay people should have the final say in the appointment of their minister. After 1650 this resulted in ministers who were unsympathetic to the new regime or unpopular (often because they were immoral or non-resident) being replaced at the recommendation of the congregation.

Shrewsbury was no exception. In 1652 there were vacancies at both St Mary’s and the Abbey churches, which were filled by two exceptional Presbyterians – Francis Tallents (1619-1708) at St Mary’s and John Bryan (1627-99) at the Abbey. [footnote 1] Both men had a similar background. Tallents went up to Cambridge University at age 16, where ‘it pleased God to call him by His grace, and to reveal his Son in him.’ Tallents said that ‘when I began to be serious, I soon became a ‘notorious’ Puritan; for which I bless God’s holy name.’ [footnote 2] Rather than being ‘notorious’ he was popular and successful, becoming a Fellow of Magdalen College Cambridge and later Senior Fellow and vice-master of the College. The famous minister Richard Baxter said that he was ‘a good scholar, a godly blameless divine, and that he was most eminent for extraordinary prudence and moderation and peaceableness towards all…’ [footnote 3] John Bryan was also a Cambridge academic, and Baxter recorded that Bryan was ‘a Godly, able preacher of a quick and active temper, but very humble’. [footnote 4] In 1659 he was persuaded to move across town to fill the ministerial vacancy at the larger and more prestigious St Chad’s church.

The beginning of persecution

After the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660 Charles II offered pardon and reconciliation for former Parliamentarians and dissenters, who would swear to keep the peace. The so-called ‘Cavalier Parliament’, however, was not so tolerant, and wanted ‘a return to local and national power of those who supported the king and the royalist cause, and an Established church in all its former style and power. They were not prepared to tolerate Presbyterianism, still less Independency, Anabaptism or Quakerism’. [footnote 5] Both Francis Tallents and John Bryan were presented at quarter sessions in March and October 1661 and warned ‘for not reading divine service and the Book of Common Prayer on the Lord’s Day’. For taking no heed of these warnings and continuing to preach openly both men were imprisoned in the Castle for a short time in July 1662. [footnote 6]

‘The Great Ejection’

The July 1662 Act of Uniformity of Public Prayers ‘required all ministers who wished to remain within the Established Church to assent to the 39 articles… [and] accept that only Episcopal ordination [by a bishop] was valid.’ [footnote 7]Those ministers who would not conform to this act were ejected on 24th August 1662, among them Bryan, Tallents and Richard Heath of St Alkmund’s. [footnote 8] Throughout the country over 2,000 of the best and most godly ministers lost their positions in what became known as ‘the Great Ejection’.

Further persecution

Two years later, the first Conventicle Act of May 1664 forbade five or more people to meet for worship outside the Church of England. Lord Newport, Lord Lieutenant of Shropshire (right), paid informers to infiltrate religious gatherings, to report on those who refused to receive the sacrament, kept their hats on in the service or failed to follow the prescribed liturgy. These were brought up before the church courts. How rigorously these laws were enforced depended on the sympathies of the local magistrates. The evidence from Shrewsbury is that magistrates were quite lenient, which was not the case in other parts of the country. Perhaps the best known example is John Bunyan (1628-88), who was imprisoned in Bedford for a total of nearly 15 years between 1661 and 1688. However, he used his imprisonment to good effect, writing The Pilgrim’s Progress during these years.

Realising that these measures were not really succeeding in reducing the influence of the ejected ministers, in 1665 Parliament passed the ‘The Five Mile Act’, under which ministers who would not sign the 1662 Act of Uniformity ‘were denied the liberty of coming within five miles of any parish where they had formerly been ministers, or any place where they had held conventicles or any corporate town which sent members of Parliament’. [footnote 9] So Tallents, Bryan and Heath had to leave Shrewsbury. Tallents went back to his home county of Derbyshire, Bryan to Shifnal, from where he came to Shrewsbury by night to minister to the Presbyterians, and Heath to Wellington, where he died the following year.

The ‘Declaration of Indulgence’

The king seemed uneasy with these measures, however, and in 1672 he issued a ‘Declaration of Indulgence’, which suspended the laws against dissenters, provided that their meeting-houses, preachers and teachers were licensed. In Shrewsbury some applied for licences, some didn’t. Those in prison were released. Bryan applied for a licence. Despite the Five Mile Act still being in force, a number of ministers returned to Shrewsbury, including Bryan (1672) and Tallents (1673). The local magistrates turned a blind eye to this, and even to the visit of the notorious leader of the Quakers, George Fox (left). In 1673 the King was forced to withdraw the Indulgence, but it took time to revert to the previous position, and nonconformists were prosecuted rather patchily. For example the house of Elizabeth Hunt of Boreatton was not raided until 1684, despite meetings being held there regularly between the 1660s and 1690.

Freedom at last

The first act of William and Mary when they came to the throne in 1688 was to exempt the nonconformists from all the penalties relating to Acts of Parliament dating back to 1593. This meant that they could meet openly and were not required to attend Church of England services. [footnote 10] In 1690 Mrs Hunt died and the meetings in her house were moved to Mr Tallents’ house for a year until the chapel in the High Street was built. It was formally opened on October 25th 1691, and Tallents caused to be inscribed on the walls that the meeting place was built, ‘not for a faction or a party, but for promoting repentance and faith, in communion with all that love the Lord Jesus Christ in sincerity’. Under Bryan and Tallents’ leadership the church flourished and also opened an academy, because nonconformists were barred from entering the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge.

John Bryan died in 1699, and was buried in Old St Chad’s. Tallents died in 1708, aged 88. He was buried at St Mary’s in the same grave as his first wife, who had died over 50 years before. Both men had suffered much, choosing danger, poverty, imprisonment and ridicule rather than to go against their conscience. Tallents used to say that ‘we hope that many of [the ejected ministers] got good by our sufferings, were purified by them and our hearts made better by our sadness. God would show us that he can carry on the work another way, and multiply his people, even when they are in affliction, and make even the sufferings of his ministers turn to the furtherance of the Gospel of Christ.’

There is no doubt that ‘The Great Ejection’ of 1662 had a profound effect on Christianity in this land. Here is the conclusion of one expert – ‘Whatever we may think were the weaknesses of some Puritans, there can be no denying that it was their activity which had led to a period in which theology was valued, when sound doctrine and fervent gospel preaching were esteemed, and when Bible reading and spiritual hunger were characteristic of large portions of the common people. It is equally true that after the silencing of the 2,000 we enter an age of rationalism, of coldness in the pulpit and indifference in the pew, an age in which scepticism and worldliness went far to reducing national religion to a mere parody of New Testament Christianity.’ [footnote 11]

Footnotes

[1] HE Forrest, The Old Churches of Shrewsbury, Wilding and Son, 1922, pp. 23ff and 58ff

[2] Matthew Henry, A Sermon preached at the funeral of Rev Francis Tallents, minister of the gospel in Shrewsbury, who dy’d there April 11th 1708, in the eighty ninth year of his age. With a short account of his life and death, SA D92

[4] Thomas Phillips, History and Antiquities of Shrewsbury, Hulbert’s Edition, 1837, SA 6004/1496; Janice V Cox, The People of God, Shrewsbury Dissenters 1660-99, Part 1, Shropshire Records Series, Vol. 9, 2006

[6] RF Skinner, Nonconformity in Shropshire, 1662-1816, Wilding and Son, 1964, p.104

[8] The significance of the chosen date – St Bartholomew’s Day – was not lost on the ejected ministers, it being a reminder of the massacre of anything up to 30,000 French Protestant Huguenots on St Bartholomew’s Day 1572

[11] John Murray, Ed., Sermons of the Great Ejection, Banner of Truth, 1962, p.8