Benbow is a popular place name in Shrewsbury – we have Benbow Quay and Benbow Close, both in Coton Hill, and Benbow Business Park off Harlescott Lane. These are named after Admiral John Benbow (c1652 – 1702), an important figure in the history of the Royal Navy. [footnote 1] This article, however, is about another John Benbow.

This John Benbow (1623 – 1651), who was probably the Admiral’s uncle, was the second son of William Benbow, a tanner of Mardol, and a burgess of Shrewsbury. [footnote 2] During the Civil War he fought for the Parliamentary side, becoming a Lieutenant in their cavalry. In 1645 he became celebrated for his part in the capture of Shrewsbury from the Royalists.

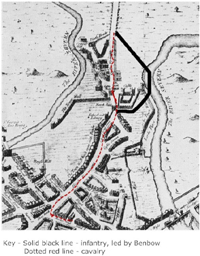

Shrewsbury had been a Royalist stronghold since the beginning of the Civil War, protected by a significant garrison in the Castle. By early 1645, however, the garrison had to be weakened to shore up the Royalist cause in Chester, and the Parliamentarians, based in Wem, felt that they had a chance to take Shrewsbury. The accounts of exactly how they did so are conflicting, but the following is my understanding of the story. At around 4am on the morning of Saturday February 22nd 1645, the Parliamentary forces gathered at the end of Castle Foregate. [footnote 3] Most of the infantry then cut across the fields to the River Severn where 30 of them embarked in a boat specially enlarged for the purpose. [footnote 4] They then rowed up the river and landed the men below the castle before returning for more. The Royalists had strengthened the defences along the river with wooden palisades, but the Parliamentarians were prepared for this, and had brought carpenters and tools to cut down the palisades. While they were doing this, a sentry in the Castle heard them and naturally questioned who they were. When they called out “Friends”, the sentry seemed unclear what to do, first arguing with them and then going off to fetch his corporal for advice.

By the time he had done so, and sounded the alarm, 15 minutes had elapsed and the palisades had been breached. Now under fire from the Castle, Lieutenant Benbow led the troops round the bottom of the Castle walls towards Castle Street. Here they encountered the town wall which they climbed with the help of light ladders they had brought for the purpose. They then broke down the Castle Gates and let the Parliamentary Cavalry in. [footnote 5] The cavalry hurried down Pride Hill to join the rest of the infantry who were engaging Royalist troops in the Market Place. After a brief, but fierce, battle the Royalists were overcome. Meanwhile, using the local knowledge of men such as Benbow, many of the leading citizens were taken prisoner while they were lying in their beds. Realising their position was hopeless, the castle garrison surrendered later in the day. Most of them were allowed to march off to Ludlow, but the thirteen Irishmen among them were summarily hanged. [footnote 6] The contemporary sources I have used say nothing about a ‘traitor’ who is alleged to have opened St Mary’s Watergate to let the Parliamentary forces in. It may be true, or it may have been an invention as an excuse for the fact that the town was taken so easily.

For his part in this victory Lt Benbow was immediately promoted to Captain and continued to serve with distinction until the end of the war. But later events took a surprising turn. In 1651 the future Charles II landed in Scotland where he was proclaimed king. He gathered a 2000-strong army, and in August he marched south to reclaim England for the crown. [footnote 7] But even amongst English royalists support for him was lukewarm, chiefly because he was allied to the Scottish Presbyterians. Undaunted, Charles pressed on, and was joined by some supporters, amongst whom was Captain John Benbow. Quite why he had changed sides we will never know. The beheading of Charles I certainly caused some to doubt the Parliamentary cause. Be that as it may, Benbow’s choice was to prove fatal. On September 3rd 1651 the Royalist army was routed by Cromwell’s New Model Army at Worcester. Charles escaped, and eventually fled to France. Benbow was not so lucky, being recaptured near Newport and taken to Chester to stand trial. Parliament had decreed that anybody who supported Charles was to be classified as a traitor, so the outcome of the trial was a formality. Benbow was found guilty, returned to Shrewsbury, and on October 16th 1651 he was shot by a firing squad on the same patch of ground under the Castle which had been the scene of his greatest triumph.

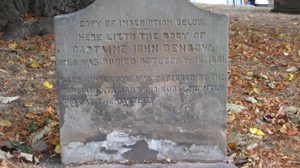

Over the years Benbow’s gravestone in Old St Chad’s churchyard became very decayed, but in 1829 a supporter renovated it at his own expense. [footnote 8] The stone is still there beside the path, but is again severely weathered. Perhaps it is time to renovate it again?

Footnotes

[1] Sam Willis, The Admiral Benbow, the life and times of a naval legend, Quercus, 2010

[2] St Julian’s Parish Register transcript, in SA, p.253; Morris’ Genealogies, Vol. 8, p.25ff, SA microfilm 149; biographies of John Benbow are, Robert Love, Shropshire Magazine, Nov 1970, p.22 and WT Bryan, Shropshire Magazine, August 1979, p.26. The former article contains much speculative material.

[3] Owen and Blakeway, A History of Shrewsbury, 1825, Vol. 1, p.449ff

[4] The Letter Books of Sir Samuel Luke, 1644-5, London HMSO, 1963, p.164; this source has been used for the rest of the paragraph.

[5] Bryan, op. cit.; Richard Gough, The History of Myddle, Penguin 1981, p.267

[6] Owen and Blakeway, pp.452-455

[7] Auden JE, Shropshire and the Royalist Conspiracies between the end of the First Civil War and the Restoration, 1648-1660, TSAHS, 3rdSeries, Vol. X, p.87-168

[8] Diary of Henry Pidgeon, 18.11.1829, SA 6001/3058