Changing the religious beliefs and behaviour of people may take a long time, especially in a naturally conservative place like Shropshire! The story of Thomas Ashton (c1500-78) illustrates how one man can have a significant part in bringing about these changes.

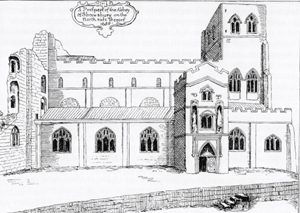

Henry VIII (reigned 1509-47) broke away from the Roman Catholic Church in 1534, proclaiming himself as head of the Church of England. He did this mainly for personal and political reasons, his theology remaining largely Catholic. He also wanted to destroy the authority of the Pope in England, so he dissolved the monasteries and other religious houses, since they were answerable directly to Rome. Shrewsbury Abbey was dissolved in 1540. It was evidently in a rundown state (a report stated that there was neither inventory accounts nor infirmary; the roof over the high altar was falling down, and masses were neglected [footnote 1]). Its loss does not seem to have been deeply felt in the town; a pension of £80 was assigned to the abbot and £87 6s 8d to the 17 monks [footnote 2]. The Reformation proceeded slowly in Shrewsbury – many images and shrines were supposed to be removed from the churches and an English Bible was placed in them, but it is likely that committed Protestants were few in Shropshire and the majority of both clergy and laity remained Catholic at heart [footnote 3].

Edward VI (reigned 1547-53) had been brought up as a Protestant, his tutor being educated at St John’s College, Cambridge, which was then a centre of the Protestant Reformation. An important member of the College was Thomas Ashton, who was a fellow from about 1522-43, and bursar on a number of occasions, and therefore indirectly had some influence on the young king [footnote 4]. In Shrewsbury, there were some outward signs of the Reformation, such as the public burning of images from St Mary’s and St Chad’s churches, the ending of the Corpus Christi procession, and the use of the new prayer book. There were also some Protestants in positions of influence in the town, and they petitioned for the establishment of a school so that the youth of the town (and further afield) could develop ‘in good lerninge and godly education’ [footnote 5]. As a result, Shrewsbury Free Grammar School was begun in 1552, under the control of bailiffs and burgesses of the town.

The accession of the Roman Catholic Mary (reigned 1553-8) saw the reintroduction of Catholic beliefs and practices. Over 300 leading Protestants were burned at the stake (mostly in the south of England), while others lay low or fled abroad. Shrewsbury seems to have reverted back to Catholicism happily enough, suggesting that the reformation had hardly touched either the priests or the church leaders. For example, Edward Burton of Longner Hall, a prominent Protestant, who spent much of Mary’s reign on the run, was declined burial by the clergy of St Chad’s Church, since his will stated that ‘no mass-monger [Catholic priest] should be present at the funeral’. (In the end he was buried in the garden at Longner, and his tomb is still there. [footnote 6])

After the accession of the Protestant Elizabeth I in 1558 the new Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield was concerned that there was no Protestant preacher in the Shrewsbury and north Shropshire area. At the same time the leaders of the town realised that the School needed a new headmaster. So Thomas Ashton, whose movements during Mary’s reign are unknown, was appointed to do both tasks, arriving in the town in 1561. He was an ideal man for the job, being described both as ‘a good and zealous man towards the preferment of learning’, and by the poet Thomas Churchyard as a ‘good and godly preacher’ [footnote 7]. Ashton exercised influence in a number of ways. Most church services consisted just of the liturgy with little or no doctrinal teaching. As a licensed Protestant preacher, Ashton would have both taught the Bible at these services and probably also held regular ‘lectures’ outside service times, as was the common custom in those days. He was also involved in pastoral matters, there being records of him being asked to settle disputes by the drapers’ and mercers’ companies, as well as between private individuals. He was also actively involved in encouraging the families of prominent Protestant gentry, such as the Corbets of Moreton Corbet. Such people were immensely influential in those days, both as leaders in town and county affairs, and amongst their tenants [footnote 8].

Perhaps Ashton’s most significant influence was through Shrewsbury School, which was transformed under his leadership. During his time the school had over 290 scholars, and was later described by William Camden in his famous book Britannia as, ‘the best filled in all England, being indebted for [its] flourishing state to the provision made by the excellent and worthy Thomas Ashton. Besides the children of the gentry of this county and North Wales, many of the first people of the kingdom send their sons there.’ [footnote 9] Among these were Philip Sidney and Fulke Greville, two of the most important men of the Elizabethan era, who joined the school on the same day in 1564. Ashton himself wrote Greek and Latin textbooks, but perhaps he is best remembered for his Whitsuntide plays, performed in the Quarry, in a semi-circular amphitheatre where the swimming pool now is, which had been used for mediaeval miracle dramas [footnote 10]. Ashton’s plays also had religious themes, the reformers believing that drama as well as preaching was an appropriate means of spreading the truths of the gospel. Ashton’s plays were hugely popular, with audiences coming from far afield. It is even recorded that in 1565 ‘Queen Elizabeth made progress as far as Coventry intending for Salop to see Mr Ashton’s play, but it was ended’ [footnote 11]. Churchyard described one of the plays as being watched by 10,000 men; while this is probably poetic licence, it is likely that the audience did reach into the thousands.

Ashton retired as headmaster of Shrewsbury School in 1571, by which time there were a number of other Protestant preachers in the town, and the Reformation was well established. Despite becoming tutor to the son of the Earl of Essex, as well as travelling to the north of England and to Ireland on court business, he continued his involvement with Shrewsbury. He was successful in increasing the endowments to the School, for which he drew up a new set of ordinances or rules for its governance, which were published just before he died in 1578. His influence in the town is summarised by a contemporary, who recorded, that one of his last acts ‘was to visit [Shrewsbury] when he preached a farewell sermon to the inhabitants of the town, after which the ‘godlie [sic] father’, accompanied with the tears and blessings of Shrewsbury, returned to Cambridge, near which he died at the end of a fortnight.’ [footnote 12]

Footnotes

[1] Barbara Coulton, Regime and Religion, Shrewsbury 1400-1700, Logaston Press, 2010, p.35

[2] Nigel Baker, Shrewsbury Abbey, a mediaeval monastery, Shropshire Books, undated p.14

[4] Bill Champion, “In depth” Thomas Ashton (died 1578), headmaster of Shrewsbury School, http://www.discovershropshire.org.uk/html/search/verb/GetRecord/theme:20061004111708, accessed 12.6.2013

[6] JB Blakeway A History of Shrewsbury Liberties, Longner, Trans Shrops Arch Soc, Vol. 6, 1894, pp.381ff. The inscription on the tomb reads, ‘He, like Jesus Christ in a garden laid,/ Where he shall rest in peace, till it be said –/“Come faithful servant, come, receive with Me/ A just reward for thy integrity.”

[7] CW Radclyffe, Memorials of Shrewsbury School, 1843, SA 5447/2