Blakeway Mews is a tiny cul-de-sac in Gains Park, Shrewsbury, but behind the name stands one of the giants of Shrewsbury history.

John Brickdale Blakeway (1765-1826) was born in Shrewsbury, his father being a prosperous merchant. He went first to Shrewsbury School and then on to Westminster, from whence he went up to Oxford. [footnote 1] At Oxford he distinguished himself as a Latin and Greek scholar (later he would also teach himself Hebrew), and after Oxford went into the legal profession, being called to the bar in 1789. At that time one had to support oneself to become a successful barrister, so when his father became bankrupt he found that this was no longer possible. He therefore retrained for the Christian ministry, and was ordained in 1793.

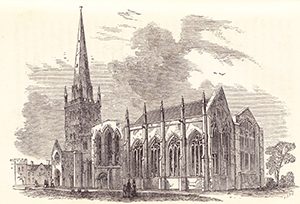

In those days obtaining a vicar’s appointment depended largely on one’s connections. Through his uncle Rev Edward Blakeway, John Brickdale became Vicar of St Mary’s Shrewsbury in 1794 and in addition became Vicar of Neen Savage in south Shropshire and Felton in Somerset. In 1800 he also became Vicar of Kinlet, Shropshire. Such ‘pluralities’ were not uncommon in those days – they often resulted in vicars living in considerable luxury while overworked and underpaid curates did all the work. In fairness to Blakeway, however, by 1816 he had given up all but St Mary’s and remained actively involved in the work of that church until his death.

Despite a speech impediment his preaching was well-respected and he was known for his generosity towards the poor. [footnote 2] But it is not for his Christian work that he is now remembered, but as an antiquarian, and as the writer, with his friend Archdeacon Hugh Owen, of Owen and Blakeway’s History of Shrewsbury. This is a reliable and still-used reference book (it is now available online for those not rich enough to afford a copy!). Blakeway amassed an enormous number of original documents which he used in his research, which is why it is so valuable. Henry Pidgeon rightly noted at the time that, ‘[The History] will be highly prized by every true Salopian and lover of our domestic history for the minute detail and great depth of research and learning which it manifests throughout, and which cannot fail to obtain for him and his worthy friend and colleague the honour and gratitude of subsequent generations.’ And so it has turned out.

Blakeway was not, however, just a dry antiquarian. Tall and stout, he usually had a smile on his face, and was a familiar figure striding around the vicinity of St Mary’s. His obituarist writes that, ‘though extremely studious, he was no less fond of society than of his books, and was hardly ever without staying company in his house… He was a most dutiful and affectionate son, a kind and attentive husband, [and] an indulgent master… Above all, he was a most faithful and invaluable friend [and] the writer…learned more from him than he did from all the books that he has ever read.’ [footnote 3]

Another writer recalled that after Samuel Butler arrived in Shrewsbury as Headmaster of Shrewsbury School, ‘there arose a little society, among the most prominent of whom were Butler, Blakeway, Owen and the Rector of the Abbey. They and their wives took assumed names of mediaeval character, calling one another Brother or Sister, and frequently writing mock Chaucerian letters to one another… Mr Blakeway was evidently the life and soul of the society.’ [footnote 4]

In 1822 Blakeway and Owen, embarked on their monumental History of Shrewsbury. Early in 1826 Blakeway developed some sort of tumour around the hip. Surgical treatment failed, and he died just as the second and final volume was going through the press. It is said that his death occurred ‘almost without a sigh and nearly without losing that smile which was so peculiar to him.’ [footnote 5]There is an impressive monument in his honour in St Mary’s.

Footnotes

[1] Basic biographical details from Gentleman’s Magazine, 1826, p276ff and Dictionary of National Biography

[2] Henry Pidgeon’s diary, SA 6001/3056, 10.3.1826ff

[3] Gentleman’s Magazine, op cit