God has been at work in our town for hundreds of years! Next year is the bicentenary of the coming of the first Primitive Methodists (popularly known as ‘Ranters’!).

Beginnings

The Primitive Methodists were a group who sought to revive the Methodist Church at the beginning of the nineteenth century, as they felt it had become too middle class and respectable.[1] The first meetings were in the Potteries in 1807, and the movement was led by Hugh Bourne and William Clowes, ordinary working men who attracted other men and women of the same background. ‘Prims’ were also characterised by great fervency in prayer and oratory and a desire to reach those outside the churches. The movement spread rapidly and soon reached Oakengates, now part of Telford.

1822

In 1822 a Primitive Methodist Society was formed in Shrewsbury, and in May it was visited by Miss Sarah Spittle from Oakengates. She wrote: ‘Sunday 30th, I preached three times to very large congregations… There are forty four in Society and there is likely to be a good work.’[2]

At the beginning of August the group was visited by James Bonser, who reported:

‘I was in Shrewsbury on Sunday last, and found the work of God prospering. We have received 60 members in this short time. Last Sunday, however, I met with some opposition… At two in the afternoon I came into [Shrewsbury], and hearing that hundreds were met together to be hired for the harvest work, I resolved to go and try to engage some of them for my Master. There was a large congregation, and the people were very attentive, but when I had nearly done preaching, the Mayor sent a constable to fetch me to the Town Hall. There I was told that if I would find bail never to preach there any more, I should be set free. Refusing to do this, the Mayor committed me to prison till the sessions. I went singing through the streets to the prison, hundreds following me. Many wept much, and when I bade them farewell, the town seemed all in confusion. I was in prison from about half-past four o’clock till half past twelve next day. [Bonser recorded elsewhere that he was brought no less than eight breakfasts by well-wishers that morning!] Prayer was made for me at the different chapels, and when brought before another magistrate on Monday, he set me at liberty. I preached on the Monday night. I had not quite all the people in Shrewsbury to hear me, but I had many of them. The occurrence has done us a deal of good in this town.’

Following this, ‘the humble missionaries of the Primitive Methodist body pursued their self-denying labours among [the inhabitants of Shrewsbury] with…success. Many vile sinners were reclaimed from their vicious practices through their instrumentality, and gave evidence of having become new creatures in Christ. The society flourished encouragingly, and soon became the head of a branch of the Oakengates circuit.’

1823

Local historian Henry Pidgeon was both scandalised and fascinated by the Ranters. Here are two extracts from his diary.

Monday June 2nd – Shrewsbury Show – ‘Our ancient pageant, called the Show, was celebrated with more spirit that has been known for many years… ‘Soon after the civil authorities had set out for Kingsland, several males and females of a sect who last year introduced themselves into our town under the title of Primitive Methodists or ‘Ranters’, assembled in the Market Hall, and began singing, after which their preachers offered up a prayer, and before it was concluded, two drummers and a fifer, belonging to a Recruiting Party, commenced their music, to ‘out noise’, if possible, that of the Ranters and disperse them. And really the ‘music of the drum’, the singing of the Ranters, and the noise of the rabble was a scene quite ludicrous. In the midst of all, however, the Ranters began their ‘exhortation’ or sermon, levelling their observation chiefly against the attendants of the Show, whom they asserted were in ‘the broad way’, holding out in the most threatening and plainest language the punishments which would be inflicted on such transgressors. The confusion and noise however increasing, the fanatical spirit of the Ranters became excited and their enthusiasm burst forth, not in love, but in anger. A general scuffle ensued, which ended in several battles, the good people dispersing, doubtless to a place of greater security.’[3]

Tuesday 3rd June – ‘A scene similar to the above took place this day. The two preachers however were taken before the magistrates.’[4]

Their own building – 1826

The society grew rapidly, meeting in rented premises, such as a Malthouse in Barker Street. By 1826 they were in a position to buy a chapel originally built for the Sandemanian Baptists in Castle Court, Castle Street for £850.[5] Local historian Henry Pidgeon recorded the event –

Sunday June 4th – ‘The chapel in Castle Court was opened for public worship by the Primitive Methodists, when three sermons were preached in the course of the day, and on the following day two more, that at night by Rev M Kent, Baptist minister. The collections made after the services amounted to £25 1s 4d.’[6]

Offending polite sensibilities

Despite now having a building, the Primitive Methodists continue to actively preach out of doors. Pidgeon recorded that on Sunday August 6th – ‘The Ranters held their annual meeting of preaching out of doors in the timber yard on the site of the Dominican Friars.’[7]

The Society was also active in support of ‘missionary’ work beyond Shrewsbury, having a particular concern for Ireland. Pidgeon recorded that on Sunday December 24th – ‘Two sermons were preached in the Primitive Methodist Chapel, Castle Court ‘in aid of the fund established to support missionaries’, that in the morning by a female [his underlining] named Hannah Farr, and in the evening by a W Leigh from Oaken Gates. The Missionary meeting was held…in the evening of Christmas, a person named ‘Jones’ took the chair. The collections amounted to upwards of £6 0s 0d.’ Notice how offended Pidgeon was (and probably most of the male population too!) that a ‘female’ was allowed to preach, and how snooty he was that a nobody called ‘Jones’ was allowed to preside at the meeting.

‘Enthusiasm’

Henry Pidgeon continued to report disparagingly on the ‘Ranters’. On 5.8.1827 he wrote of their annual camping meeting on Silk’s Meadow ‘where the enthusiasm so peculiar to the sect was exhibited with vengeance!’[8] [his emphasis and underlining] On Easter Sunday April 11th 1830 he reported that the Primitive Methodists…‘began their public services as early as 6 o’clock a.m. In the course of the day several declamations were made by them in the open air, and at night, many, I am assured on the best authority, ranted in their meeting house until a late hour with their coats off, using such violence and noise on the subject, ‘Lord, save the world’ that the perspiration literally ran from their faces. Several women fainted!!!’[9] Such displays of religious fervour were also an offence to Pidgeon!

A centre for evangelism

In 1824 the Shrewsbury church sent Samuel Heath to open a mission in Wiltshire.[10] This was so successful that by 1826 it had become a circuit in its own right. Closer to home, in the 1830s the Shrewsbury church established a circuit based on Bishop’s Castle, which became the ‘mother’ of circuits in Church Stretton and Clun, and a circuit in north Shropshire based on Hadnall.[11] The Minsterley circuit was also started from Shrewsbury. Less successful were forays into Wales, probably because of distance and language barriers, but from 1832 a mission was started in the north of Ireland, resulting in a chapel being built in Belfast in 1836.

The struggles of a young congregation

In the Shropshire Archives there are a number of letters written to the leaders of the Shrewsbury Primitive Methodist Church in 1836/7 which provide an insight into the challenges that they faced.[12] The letters were from John Hancock, a member of the ‘General Committee’, to John Moore, presumably the leader of the congregation, who is described as a ‘preacher’.

Troubles with workers

The letter of Dec 6th, 1836 discusses the resignation of Thomas Grafton, presumably a travelling preacher, and his wife from the movement. The advice was the equivalent of ‘let him go, there’s nothing you can do to stop him’. But they were to make every effort to avoid ‘rupture’, presumably division in the Church, which is a reminder that such a young enthusiastic congregation could become divided. The letter of Sept 30th 1837 discusses how the church should react after a Brother John Lyth, who had been sent as a missionary to Ireland, came back after just 10 days with a ‘rupture’, presumably the effects of a painful hernia. The general committee felt that it was a very inadequate reason to come back, using the expression he ‘runs away’. They did not recommend any financial contribution towards his return journey, but would not complain if any members of the society wanted to on compassionate grounds. They urged great frugality at all times.

Heating and lighting

It was one thing to be meeting in a purpose-built chapel, but quite another to be able to afford to run it! So Mr Moore had asked the General Committee in January 1837, ‘what do we do if we do not have money for heating and lighting, despite having taken up an offering?’ The answer was to take up another offering! The committee encouraged special collections for heating and lighting and Sunday Schools (saying that the Sunday School offerings were always well subscribed). Everyone in the movement was probably poor, but a bit of sympathy might not have gone amiss! There was better news in August, however, when the committee wrote to say they were giving £8 to help with the Irish mission. They also said that Hugh Bourne, one of the leaders of the movement, had been given a gift from a well-wisher – £2 was for the Shrewsbury circuit and £2 for their Irish mission.

Prayer and fasting

The young movement needed great support in terms of prayer. The general committee underlined this, urging, ‘Let diligent prayer for the circuit’s prospering be diligently made to Almighty God in and by every society and congregation.’ And, ‘If the circuit judge it proper, let a fast day also be appointed on the same account’ (August 12th, 1837). This is exactly what Henry Pidgeon had observed.

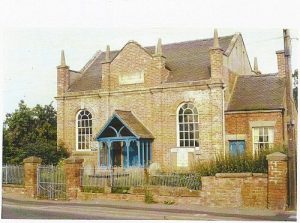

Over the succeeding decades the Primitive Methodists grew steadily. In 1863 the meeting place in Castle Court was enlarged and rebuilt.[13] By 1878 the Shrewsbury Circuit consisted of 7 churches and a number of meeting places, usually cottages. In that year the one in Belle Vue decided to erect a building, which is still an active church.

Finding out more

If you are interested to learn more about the history of Primitive Methodism, there is an interesting museum at Englesea Brook, not far from Crewe. To find out more, visit their website.

Footnotes

[1]Joseph Ritson, The Romance of Primitive Methodism, Primitive Methodist Publishing House, 1909

[2] John Petty, The History of the Primitive Methodist Connexion from its origin to the Conference of 1859, London, 1860, pp.136-137; see also, 125th Anniversary booklet of Belle Vue Methodist Church, 2004

[3] Henry Pidgeon, Salopian Annals 1823, Shropshire Archives (SA) 6001/3055

[5] Janice Cox, Non-Conformist Chapels and Meeting Houses in Shrewsbury in the Nineteenth Century, Transactions of Shropshire Archaeological and Historical Society, LXXII, 1997, p.74

[6] Henry Pidgeon, Salopian Annals, Vol. IV, 1826, SA 6001/3056

[8] Henry Pidgeon, Salopian Annals, Vol. V. 1827, SA 6001/3057

[9] Henry Pidgeon, Salopian Annals, Vol VII, 1830, SA 6001/3059

[10] https://www.myprimitivemethodists.org.uk/content/place-2/shropshire-2/castle_court_chapel_shrewsbury_shropshire

[11] https://www.myprimitivemethodists.org.uk/content/place-2/shropshire-2/hadnall_circuit_shropshire