No prizes for guessing what Battlefield Road and Battlefield Way refer to! But who exactly was the battle between, and why was it in Shrewsbury? The aim of this article is to retell the story of the battle using nearly 40 street names to guide us. These streets are predominantly in Harlescott Grange and the Battlefield Enterprise Park, but some are in Greenfields.

Henry, Duke of Lancaster (Lancaster Road) seized the throne from Richard II in 1399, becoming Henry IV (Henry Close). He also organised the murder of his predecessor, so he was regarded by many as a usurper, and his reign was characterised by unrest. Indeed, Shakespeare has him say the famous words ‘uneasy lies the head that wears a crown’. [footnote 1] Some of Henry’s chief allies were the Percy family (Percy St), the senior member of which was the Earl of Northumberland (Northumberland Place). His eldest son was Sir Henry Percy, nicknamed ‘Hotspur’ (Hotspur St and Park), on account of his impetuous bravery and horsemanship. The Percies guarded the northern border against the Scots, and the king also enlisted Hotspur to do the same in Cheshire, to repel the Welsh led by Owain Glyndŵr (Glendower Court). [footnote 2] So Hotspur became popular in the area, especially with the Cheshire Archers (Archers Way), who had formed a personal bodyguard to Richard II, but had been disbanded by Henry IV.

By 1403 the relationship between the king and the Percies had cooled to such an extent (chiefly over the failure of the king to pay for the services they had rendered) that they planned rebellion. Because of the threat from the Scots, Hotspur had to leave most of his forces in the north, before riding down to Cheshire to raise a new rebellious army. Amongst the leaders of this army were knights (Knights Way) such as Sir Richard Vernon (Vernon Drive), Sir Thomas Grosvenor (Grosvenor Green), various members of the Massey family (Massey Crescent), Sir Peter de Dutton (Dutton Green), John and Madoc Kynaston (Kynaston Road), and Thomas Hodgekynson (Hodgkinson Walk). [footnote 3] Hotspur also made a pact with his former enemy Glyndŵr that the Welsh would join him at Shrewsbury to fight their common enemy. This army then set off for Shrewsbury, whose castle was garrisoned by a force under the command of the king’s eldest son, the 16-year-old Henry, later Henry V. Assisting him was Thomas Percy, Earl of Worcester (Worcester Road), Hotspur’s uncle, but on hearing of Hotspur’s approach he deserted to Hotspur’s side, bringing with him nearly half of the Prince’s fighting force.

Knowing nothing of this, the king was at the same time marching north with an army to help the Percies against the Scots. On July 12th 1403 the king reached Nottingham, where he learned of the treachery of the Percies. The king was initially unsure what to do, but one of his commanders, the Scottish Earl of March, George Dunbar (Dunbar), urged him to get to Shrewsbury as quickly as possible to relieve Prince Henry. On July 20th Hotspur arrived at the northern gates of Shrewsbury, but was dismayed to find that the king had already entered the town by the English Bridge and his standard was flying above the Castle. Hotspur therefore withdrew to Berwick (Berwick Road, Avenue and Close) where he spent the night.

Realising that he had Hotspur on the back foot, and that his army outnumbered the rebels, the king marched (March Way) out of Shrewsbury the same evening, forded the river at Uffington and set up camp near Haughmond Abbey. The exact numbers of the two armies has been the subject of much disagreement, but a tentative estimate is 10,000 for the king and 7,000 rebels. Members of the king’s forces who have streets named after them were Edward, Duke of York (York Road), Edmund, Earl of Rutland (Rutland), John Beaufort, Earl of Somerset (Beaufort Green), Thomas Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel (Fitzalan Road), Edmund, Earl of Stafford (Stafford Drive), Sir Thomas Corbet (Corbet Close), Sir Thomas Langford (Langford Green), Richard Horkesley (Horksley), Sir Hugh Mortimer (Mortimar), Sir Reginald Mottershead (Mottershead), Thomas Strickland (Strickland), Sir Thomas Wendesley (Wendsley Road), and Sir Richard Hussey (Hussey Road). One character who wasn’t there was Sir John Falstaff, Shakespeare’s fictitious hero, to whom he gives a significant part in the Battle of Shrewsbury, and who is remembered locally by Falstaff Street.

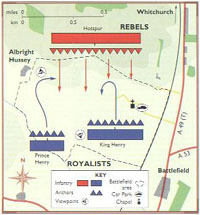

The next day, Thursday July 21st 1403, [footnote 4] Hotspur, realising he would have to stay and fight, deployed his army along the top of the low ridge that runs to the west of what is now the A49 as it leaves Shrewsbury. The king mustered around what is now Battlefield Church and further west; he himself commanded the main body of the force, with Prince Henry leading the left flank and the Earl of Stafford the right. Neither side seemed keen to begin the fight, and Thomas Prestbury (Prestbury Green), Abbot of Shrewsbury, and Ralph, Abbot of Haughmond attempted to mediate. [footnote 5] In the end compromise proved impossible, and battle commenced in the early evening.

This was the first time that the deadly English longbow (Longbow Close) had been used in a battle between English forces. As soon as the armies came within range, the superior power of the Cheshire Bowmen inflicted terrible casualties on the king’s forces. The king’s men went down ‘like apples fallen in the autumn’, as one chronicler put it. The Earl of Stafford was killed, and the right flank of the king’s army disintegrated, many of the soldiers fleeing. An arrow entered the left side of Prince Henry’s face beside his nose, lodging at the base of his skull, but, amazingly, he was able to remain in the field. The arrow storm forced the king’s forces back roughly to where they had started, but as the supply of arrows dwindled, the impetuous Hotspur sought to drive forward his advantage by leading a cavalry charge whose aim was to kill the king himself. The king, however, was not easy to find, as he wore a plain knight’s armour, while several of his household acted as decoys dressed in royal livery. Just at this critical moment Hotspur was killed; one tradition is that his death was caused by an arrow in the face, while others claim that he was cut down, perhaps by Sir Richard Sandford (Sandford Avenue), a Shropshire knight. [footnote 6] When it was realised that Hotspur was dead, the rebel forces became disorganised, and the king’s left flank commanded by Prince Henry was able to encircle and decisively defeat them. Glyndŵr and the Welsh were not able to arrive in time to support their allies – the story that Glyndŵr watched the battle from an oak at Shelton is probably a myth.

How many died, either on the field or later of their wounds, is unknown, but it must have been several thousand. ‘Those who were present,’ wrote one chronicler, ‘said they never saw and never read in the records of Christian times of so ferocious a battle in so short a time, or of larger casualties that happened here.’ It is said that around 1600 men were placed in a mass grave under what is now Battlefield Church. Others were probably buried where they lay, while those of superior status were taken to their homes for burial. This included Hotspur, whose body was initially interred at Whitchurch. There is a local tradition that Featherbed Lane was so-called from being a place where the wounded were tended after the battle, but the name probably just signifies a soft or muddy thoroughfare. [footnote 7]

After the battle, three of the ringleaders of the revolt, the Earl of Worcester, Sir Richard Vernon and Sir Richard Venables, were captured and summarily executed in the centre of Shrewsbury. The king, fearing that rumours would spread that Hotspur was still alive, had his body exhumed, pickled and displayed in Shrewsbury market place. Then it was beheaded and quartered; the head was placed on a stake in York, and the quarters sent round the country to dissuade further rebellion. These events are recorded on a plaque which is now situated at the junction of St Mary’s St and Castle St. Hotspur, however, lives on in a curious way. The Earls of Northumberland owned much land in north London, and when a new football club was founded there in 1882 it was named Tottenham Hotspur in his honour.

While this was going on, Prince Henry’s life was in mortal danger in Kenilworth Castle. The wooden shaft of the arrow that had pierced his face was broken off, but the metal tip remained embedded in the base of the skull, and inevitably infection set in. But an incredibly brave and skilful surgeon, John Bradmore, enlarged the wound with probes soaked in honey as an antiseptic, and extracted the arrowhead, using a tool he designed himself. [footnote 8] The whole procedure has recently been recreated, and can be viewed on youtube.

Why not visit the battlefield for yourself? You can access it via the northern ring road, or from Battlefield 1403 – more information is available on their website . There you can view an interesting exhibition and also get the key to Battlefield Church, which has more information about the protagonists in the battle.

The author is grateful to Dorothy Nicolle for help with the article.

Footnotes

[1] Henry the Fourth, part 2, act 3, scene 1

[2] Key sources are – John Barratt, The Battle of Shrewsbury, www.militaryhistoryonline.com/medieval/shrewsbury/, accessed 19.11.2013; http://shropshirehistory.com/medieval/batshrewsbury.htm, accessed 22.11.2013

[3] Information from Battlefield Church

[4] http://www.searchforancestors.com/utility/dayofweek.html, accessed 22.11.2013

[5] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Prestbury, accessed 22.11.2013; http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=39927, accessed 22.11.2013

[6] Sandford family memo via Dorothy Nicolle

[7] John L Hobbs, Shrewsbury Street Names,Wilding, 1954

[8] The full text of Bradmore’s report is at – http://infospigot.typepad.com/infospigot_the_chronicles/2007/06/further-inquiri.html(accessed 22.11.2013).