It is hard to believe now that Shrewsbury was once important in the manufacture of lead. These lead works were owned by the Burr family and were situated near the river Severn in Kingsland, just downstream from Kingsland Bridge. Hence the area is now called Burr’s Field.

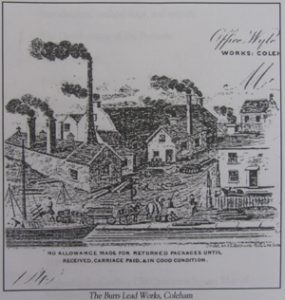

The Burrs were a London-based family of plumbers, one of whom, Thomas, decided to move to Shrewsbury, arriving in 1813. [footnote 1] He set up in business in a large building on the corner of Beeches Lane and St Julian’s Friars, where the Century Cinema used to be. Having patented ‘Burr’s Lead Squirting Press’, he was able to make lead pipes more cheaply and efficiently than his competitors and his business prospered. In 1829 he bought Charles Bage’s old linen weaving factory in Kingsland and gradually moved his business there, enlarging the site until he was able to sell his original works. The most impressive feature of the factory was a shot tower, which was 150ft high, 30ft in diameter at its base and 12ft in diameter at the top. [footnote 2] (As its name suggests, a shot tower is used to produce lead shot for gun cartridges. Molten lead is passed through a copper sieve at the top of the tower, and the action of gravity then turns the shot into balls. It partly cools during its descent and is then caught in a water bath.) As well as shot and lead piping, the factory also produced lead sheets (for roofing etc.), and lead oxides for use in other industries, such as paint and cosmetics.

Thomas Burr was succeeded by his sons Thomas junior, William and George. As well as being manufacturers of lead, the family had some involvement in the Snailbeach lead mines (which produced 10% of the nation’s lead in 1872), and a lead smelting works in Pontesford. The family was also active in civic affairs, and William was elected Mayor of Shrewsbury in 1858/9.

Burr’s lead works were heavily criticised on account of the pollution they caused. One resident of Quarry Place wrote that, ‘When the wind is in a certain point the smoke is blown to the Crescent, and it is of so nauseous a description, having a metallic taste as well as smell, that it is absolutely necessary to shut the windows, and even then it is not entirely excluded…’ [footnote 3] Another resident commented that, ‘When the factory is at work the whole place is enveloped in a cloud of smoke… The manufacture of red lead is carried on in a low building, and the roof and chimney of this place can be perfectly red with the deposit.’ [footnote 4] It had been known since antiquity that lead could be poisonous, but in Victorian times the ability to measure lead levels enabled this toxicity to be better understood. Chemical analysis of the ground near the factory showed that there was about 780 grams of red lead per square foot. When one considers that the modern recommendation for a safe blood lead level is less than one 10 millionth of a gram, it is no wonder that the workers suffered early deaths from lead poisoning. [footnote 5] Even now the factory site is too contaminated to be used for agriculture or housing.

The Burrs tried to mitigate the effects of pollution, but in 1894 George decided to close the works. As the contractors were about to demolish the shot tower it collapsed – a dramatic end to 80 years of lead manufacturing in Shrewsbury. [footnote 6]

Footnotes

[1] Barrie Trinder, The Industrial Archaeology of Shropshire, Phillimore, 1996, pp.161-3; Janet Hordley, Turning all our lead into gold’, University thesis, SA q.D. 28.8

[3] W Ranger, Report to the General Board of Health …Borough of Shrewsbury, HMSO, 1854, SA D21, pp.68 -71