Scott Street, which joins Old Potts Way opposite the cinema in Shrewsbury, is so named after the Scott family, who once owned much of the land in the area. Their family seat was Betton Strange Hall, which is near the road from Shrewsbury to Pitchford; hence the continuation of Scott Street is called Betton Street (now only approached by car from Belle Vue Road).

The Scott family appears to have moved to Shrewsbury from Kent in the late 1500s, and obtained Betton Strange Hall by marriage around a century later. [footnote 1] The Kent Scotts were descended from William le Scot de Balliol (1251-1312), probably a distant relative of John Balliol, the King of Scotland ousted by Robert the Bruce. Over the years they dropped the Balliol, and became just ‘Scott’. [footnote 2]

Perhaps the best known member of the Shropshire Scott family was Jonathan (1754-1829). Born at Betton Strange Hall, he attended Shrewsbury School for a short time before going with two of his older brothers to India when he was just 13. The older boys were going out to join the army of the East India Company, and when Jonathan was 16 he, too, joined one of the native infantry regiments, rising to the rank of captain in 1778. During this period Jonathan developed an abiding interest in Indian culture and history, and he also realised that he had an amazing flair for languages. [footnote 3] He learned what was then called ‘Hindustani’, now Urdu/Hindi, ‘Persian’ (Farsi), and Arabic, as well as French. Presumably he picked up these languages through conversing with the natives, and such was his proficiency that he came to the notice of Warren Hastings, appointed Governor-General of Bengal in 1773. Hastings made Jonathan Scott his ‘Persian Secretary’, part of Hastings’ policy of respecting and working with the native culture. [footnote 4] In 1784 Scott supported Hastings in the foundation of the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal, whose aim was to further the study of oriental literature and culture.

Scott resigned his commission and returned home in January 1785, having been in India for 18 years. He married his cousin Anne Austin the following year and they had a son, who died in infancy, and a daughter. He loved being back in England, writing soon after his return that on a walk ‘I poured out my soul to God and felt true serenity of mind in gratitude to thee, O Lord, who hast permitted me to visit again my native land.’ [footnote 5] On the other hand, he also wrote that ‘the most agreeable topic of conversation I know is India and Indian friends.’ [footnote 6] Shy and retiring by nature, he lived quietly in the country at Netley, near Dorrington, and produced a series of original works and translations from Arabic, Urdu and Farsi.

From 1802-05 he was persuaded to leave the seclusion of Shropshire and became Professor of Oriental Languages at the Royal Military College, Marlow, and the East India College, near Hertford. But he couldn’t stay away from Shropshire for long, and, back home, in 1811 he completed his most famous work, the translation of what was then called ‘The Arabian Nights Entertainment’, better known now as ‘The 1001 Nights’. Such stories as Aladdin’s Wonderful Lamp, Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, and Sinbad the Sailor continue to influence our lives through Jonathan Scott’s translation, which is still freely available. So Aladdin has more associations with Shrewsbury than just a Christmas pantomime!

Jonathan Scott was described as ‘a gentleman possessed of a disposition the most kind and generous [with] extreme modesty.’ [footnote 7] He was keen to encourage young people, and one extraordinary young person he supported was Samuel Lee (1783-1852). Samuel was the son of a carpenter from Longnor, who taught himself languages from books in what little spare time he had. His talents were so prodigious that Jonathan Scott and others paid for him to go to Cambridge University, where he became Professor of Arabic, and later of Hebrew.

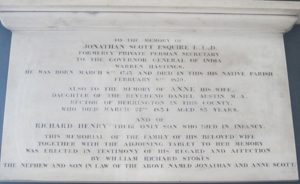

Scott spent his last days living in St John’s Row, in what is now Murivance, where he died. He was buried with his wife, son and daughter within the ruins of Old St Chad’s Church. [footnote 8]

Footnotes

[1]Joseph Morris, Shropshire Genealogy, Vol. 7, p.3649ff; William Phillips Shropshire Men, Vol. 3, p.184

[1]Dugald McFadyean, The Apostolic Labours of Captain Jonathan Scott, unknown periodical, SA CO1/1655, XLS6599; http://www.geni.com/people/William-de-Balliol/6000000000437150653, accessed 9.4.2013

[1]Obituary, Gentleman’s Magazine, reprinted in SJ 3.6.1829, and SA Watton’s Cuttings, Vol. 6, p.206 – further biographical information is from this source, unless otherwise stated

[1]Wikipedia, accessed 27.3.2013

[1]Anne Powell, ‘At the Seventh Milestone from Salop’, Letters from Jonathan Scott to his brothers and cousin, Dick, Harry and Ned, Shropshire Magazine, October 1988, pp.8-10; Nov 1988, pp.10-14, December 1988, pp.8-9

[1]Ibid

[1]Henry Pidgeon’s Diary, 11.2.1829, SA 6001/3058

[1]Memorial in St Chad’s Church