In this series we are looking at some of the entries from the diary of local historian Henry Pidgeon, written in the 1820s and 30s. Many charitable institutions at that time published an annual report. Here is one that caught his attention.

January 1829 – ‘The report for the Infant School near the Welsh Bridge for the year ending 1828 has been circulated. It states that, ‘the most essential object of Infant Schools is to render [the children] happy and tractable, to guard them from accident, and from mixing in bad company. The activity of mind and body, which forms so important a feature in the discipline of these schools has been found to be equally conducive to the health and good temper of the children.’ There are 120 children in this school, and rewards in clothing are given to those whose parents are in extreme poverty in order to encourage cleanliness and regularity of attendance.’[see footnote 1]

The historic interest of this school is that it was run by Charles Darwin’s sisters. It was founded in 1824 by his second oldest sister, Caroline (1800-88), in Frankwell, near what is now the roundabout. [see footnote 2] Caroline was supported by her sister Susan (1803-66), who became headmistress when Caroline married in 1837. At that time there was, of course, no system of compulsory education, though more children spent time in education than is sometimes thought. [see footnote 3] Many of the poor received education at Sunday schools, while in the week some were also able to attend charity schools, such as Bowdler’s, Allat’s, or Millington’s in Shrewsbury, while others paid a small pittance to attend lessons (often of poor quality) at a ‘dame school’. But there was almost nothing for infants, who could be neglected in large poor families, and hence prone to accidents and abuse, as Pidgeon’s report explained.

A letter written by Caroline Darwin’s aunt in 1824 describes what their school was like –

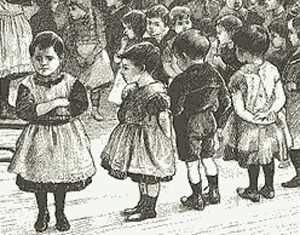

‘I have been with her [Caroline] today at her infant school. I could scarcely refrain from tears of sorrow, at seeing the little creatures, all at the word of command, drop down on their knees and say the Lord’s Prayer. They sung two hymns very tolerably, and a whole set of them, none more than four years old, seemed to me quite perfect in their multiplication table. I was quite surprised at their proficiency; not that they were all quite under command, for some of the newcomers were toddling about the room without knowing what they were about, and others were lying down upon a bed that was placed in a corner of a room for that purpose… [You] must not expect to see rosy little cherubs in white frocks and pink sashes, but on the contrary perhaps, for the most part, sickly and dirty little children.’[see footnote 4]

So how was the school financed? Pidgeon supplied the figures for 1828 as follows:

| £ | s | d | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Balance brought forward | 82 | 04 | 00 |

| Subscriptions received | 29 | 05 | 06 |

| Donations | 07 | 06 | 00 |

| Children’s pence | 19 | 06 | 10 |

| Interest | 04 | 12 | 00 |

| Total income | 142 | 14 | 04 |

| Expenditure | 69 | 01 | 10 |

| Balance in hand | 73 | 12 | 06 |

The poor paid their ‘pence’ and some well-wishers gave regular subscriptions and donations to enable the children to receive gifts of clothing, as Pidgeon reported. But what really strikes one about the figures is the huge balance in the account – maybe £10,000 at today’s prices. [see footnote 5] Where had that come from? The answer was Caroline and Susan’s father Dr Robert Darwin (1766-1848), who was by that time a very wealthy man. [see footnote 6] As well as regular support, he paid for the school to be rebuilt near the original site in 1833, where it continued until Susan’s death in 1866. [see footnote 7] After that it became part of the St George’s Church of England school in 1868. [see footnote 8] This is now converted into flats, but its doorway can still be seen.

Footnotes

[1] Shropshire Archives, SA 6001/3055

[2] Andrew Pattison, The Darwins of Shrewsbury, History Press, 2009, pp.50-1

[3] Emma Griffin, Liberty’s Dawn, a people’s history of the Industrial Revolution, Yale University Press, 2013, p 165ff

[4] Bessy Wedgwood to Sally Allen, quoted in Henri Quinn, Charles Darwin, Shrewsbury’s Man of the Millennium, private publication, 1999, p.21

[7] Millington Hospital Trustees’ Minute Books, Shropshire Archives 2133/12

[8] George Alcock, Millington’s Hospital, a brief history, private publication, 2007, p.41