Thieves’ Lane is the part of the old Shrewsbury ring road that runs between Emstrey and Weeping Cross. Emstrey in mentioned in the Domesday Book and is probably derived from the Old English ‘church on the land by the river’, but all signs of a Saxon church have long disappeared. [footnote 1] Weeping Cross also had religious connections, since it is believed to have been the site of a cross which was associated with a procession on either Ash Wednesday or Corpus Christi. [footnote 2] Thieves’ Lane followed the line of an old Roman road, and has been known by that name for about 500 years, perhaps because it was a way for robbers to avoid the main turnpike roads. [footnote 3]

It certainly lived up to its name in 1812. On 31st January the Shrewsbury Chronicle reported that

On Friday afternoon last, as Mr Thomas Hughes, a pig-drover from Bala, was returning to Shrewsbury from Wellington…he was attacked near Emstrey by two men in dark-coloured coats… He resisted, but on one of them presenting a pistol, he delivered his pocket-book containing various bills to the amounts of upwards of £100. The villains, after beating him and throwing him into a ditch, make their escape over a hedge.

On February 14th, the same newspaper contained the following –

Mr Norcombe, the collector of the post-horse duty, was stopped about 8 o’clock on Monday night at Emstrey by a footpad… The ruffian dragged Mr Norcombe from the saddle and beat him severely. Fortunately the mail coach came in sight, and the villain escaped without his plunder.

Draconian punishments (transportation or even hanging) did little to deter would-be thieves, who knew that they were unlikely to be caught, since it was well-nigh impossible to identify a stranger, especially in the darkness. Exactly this problem was reported at that time in the Salopian Journal, which recorded that a man called Rowland had been robbed on the road near Condover by a man in a corduroy jacket. ‘A man has been apprehended and examined on a suspicion of his being the robber, but his person could not be fully identified,’ the paper sadly concluded.

Law enforcement had become totally inadequate by 1812. It had been the responsibility of the magistrates for hundreds of years, and their only force ‘on the ground’ were the parish constables. A report published at about this time concluded that,

We are convinced of the incompetency of the old parish constable. He holds his office generally for a year; he enters upon his duties unwillingly; he knows little [about] what is required of him; he is scantily paid for some things, and has no remuneration in many cases. He has local connections, is actuated by personal apprehension, and dreads making himself obnoxious. His private occupations as a farmer or little tradesman engross his time, and, in most cases, render him loath to exertion as a public officer. All these drawbacks have induced a general persuasion that, in ordinary cases, the parish constable has an interest in keeping out of the way when his services are called for. [footnote 4]

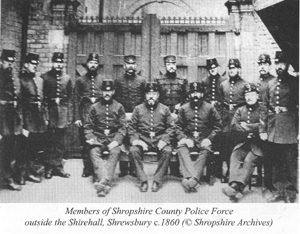

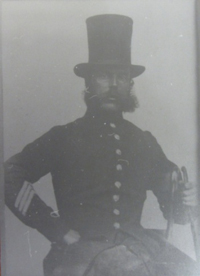

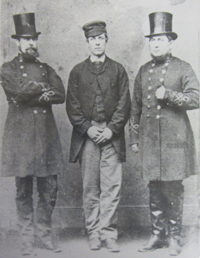

In response to such criticisms, the government required the new authorities set up by the Municipal Corporations Act of 1835 to set up local police forces. While the Shrewsbury Council agreed that such a force was a good thing, it was reluctant to spend money, and little happened. The County Magistrates, however, led by Sir Baldwin Leighton (1805-71), were much more forward, and by June 1840 they were able to report that the new rural constables had caught and charged 295 suspects in the first quarter of the year. [footnote 5] Gradually both town and county developed the disciplines of a modern force, but there were hiccups along the way. For example, the Shrewsbury Chronicle reported on April 22nd 1859 –

On Tuesday the Borough Magistrates heard a charge against James Gough, who for some months had been a member of the Borough police force. A few nights before, the sergeant on duty could not find the defendant at his post, and on making search, he was found drunk in a brothel. He was suspended at once, and has not been heard of since…

Footnotes

[1] John Hobbs, Shrewsbury Street Names, Wilding and Son, 1954

[2] Hobbs, op. cit.; Jennie Austerberry, A Glimpse of Old Shrewsbury, Wilding and Son, undated, p.47

[4] Quoted in David J Cox and Barry S Godfrey, Cinderellas and Packhorses, Logaston, 2005, p.29

[5] Cox and Godfrey, op. cit., p.50; Douglas J Elliott, Policing Shropshire, 1836-1967, Brewin Books, 1984, p.22