Last time I introduced the diary of Henry Pidgeon (1806-71), which describes a severe outbreak of measles and smallpox in Jan and February 1823. Its seriousness is vividly demonstrated by the following entry –

Feb 27th – ‘On referring to the registers of three of our four churches, it is found that there have been 70 interments in the Parish of St Chad, 56 at St Mary, and 28 at St Julian’s since the 1st of January. There were 8 graves opened in one day in St Chad’s church gardens.’

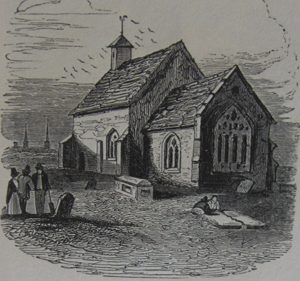

Looking at the parish registers, we find that there were 163 burials conducted in these churches during January and February 1823. Considering that the churchyards of all three churches were quite small, these figures made me wonder, ‘how did they fit all these bodies in?’ An entry in Pidgeon’s diary for the next year throws light on the situation.

Sunday May 2nd 1824 – ‘The burial ground attached to [St Mary’s] Church…has long been full and in a dirty and most irregular state. In fact, I have witnessed graves that have been made within eighteen inches of the surface of the ground, whilst the soil from repeated interments had accumulated to a considerable height up the walls of the building. It has therefore been considered advisable to lower the cemetery, and consequently many hundreds of cartloads of earth have been conveyed to a field of Dr Butler’s at Coton Hill. Although considerable improvement will be effected by this proceeding at the north, south and west entrances, whereby some inconvenient steps have been removed which caused an unpleasant descent into the church, yet the feeling mind cannot but grieve at the consequent removal of the ashes of hundreds, and view with a sort of sympathetic disgust the quantity of human bones which are continually thrown up and scattered around with apparent unconcern… At the same time it is to be lamented that places of [burial] ever should have been allowed in towns; our own having afforded a striking example of the [unfortunate] effects resulting from such a practice.’[see footnote 1]

Pidgeon’s was one of many voices raised at this time about the inadequacy of historic burial grounds, a problem which was most acute in the rapidly expanding cities. [see footnote 2] New cemeteries were established in a number of cities by private enterprise in the 1820’s to 1840’s, but these were mainly too expensive for the poor. In Shrewsbury, two small private burial grounds were opened, a Church of England one next to the Abbey (1841), and a nonconformist one beside what is now the Apostolic Church on Belle Vue Road (1852). But Parliament recognised that there was a need for public burial provision, so in 1852/3 two acts were passed which laid the legal framework that allowed the establishment of municipal burial boards to plan and run local cemeteries.

Shrewsbury’s Burial Board began in 1852. A site on Longden Road was chosen for the cemetery and, after a somewhat tortuous series of negotiations between the Church of England and nonconformist parties, the cemetery and chapel were consecrated on 26th November 1856. No doubt Henry Pidgeon was pleased to be buried there in July 1871, since when he has been allowed to ‘rest in peace’.

Footnotes

[1] Shropshire Archives, SA 6001/3055

[2] Information for this section is from Peter Francis, A Matter of Life and Death, Secrets of Shrewsbury Cemetery, Logaston Press, 2006, pp. 1-11